Advocating in a Polarized Political Environment

The opinion formation process can be discouraging, as we often cling to our beliefs even when we know we might be wrong. Instead of being guided by analysis, evidence, and intelligence, our opinions can be shaped by incompetence, overestimating our knowledge, capabilities, and opportunism. It’s essential to recognize these tendencies, especially in an era where the rapid spread of autocratization is pervasive. A troubling pattern emerges as ruling governments embark on campaigns against media and civil society, deliberately fuelling societal polarization by disseminating false information and disparaging opponents. This trend threatens formal institutions and requires advocates to navigate escalating polarization and divergent ideologies to bring about effective change.

Navigating the Challenges of Advocacy in a Polarized Society

Advocacy is the deliberate process of influencing decisions within political, economic, and social systems and institutions to make policies and processes more just, inclusive, and pro-poor (see Advocacy Toolbox, TB inserted). It involves influencing the right people and communicating ideas effectively and convincingly, recognizing that neither people nor ideas are apolitical. Policies are shaped by converging three distinct “streams”: problem, solution, and political will. The way how we navigate the third “stream” depends on whether we operate in a pluralist (participation of many groups representing competing interests in the policy process), bias-pluralist (public policy responding to the preferences of economic elites and organized business interests rather than average citizens and mass-based interest groups), or polarized context (every piece of evidence promoted by one party will be challenged by the other one). Political parties play an important role in a polarized context as they set agenda access and can determine whether change occurs.

Traditionally, experts were seen as responsible for proposing solutions (and, to some extent, problem definition), but even their behaviours and positions are hardly politically neutral in a polarised society. They may generate a “policy primeval soup” of ideas and solutions, waiting for the right problem and political moment to make them feasible. To avoid falling into the trap of a nonobjective “policy market” and policy entrepreneurship, it is essential to map expert organizations based on their alignment with academics, think tanks, and political organizations

In a polarized society, advocacy faces numerous challenges, such as building trust and credibility amid opposing views, overcoming confirmation bias hindering receptivity to different perspectives, and addressing emotion-driven decision-making that complicates constructive dialogue. Additionally, managing the overwhelming amount of information and dealing with limited funding further complicate the advocacy landscape. In such contexts, successful advocacy demands patience, persistence, and a commitment to fact-based messaging that emphasizes shared values to foster progress and change.

Implications of polarization

Advocating in a polarized context results in political, government, and representation effects.

Political effects include polarized demand for policy evidence, limited bipartisan compromise and dialogue (mainly at the technical level), and the rise of partisan political organizations that fuel and accelerate polarization. Government effects are characterized by fewer opportunities for new legislation, resulting in a severe status quo, party leaders exerting control over information flow, and policy-making becoming less objectively informed. Representation effects result in poor representation of the average citizen, leaving the median voter aside. At the same time, politicians prioritize policies catering to extended support coalitions, leading to a “policy blind spot” where citizens struggle to distinguish between alternative proposals.

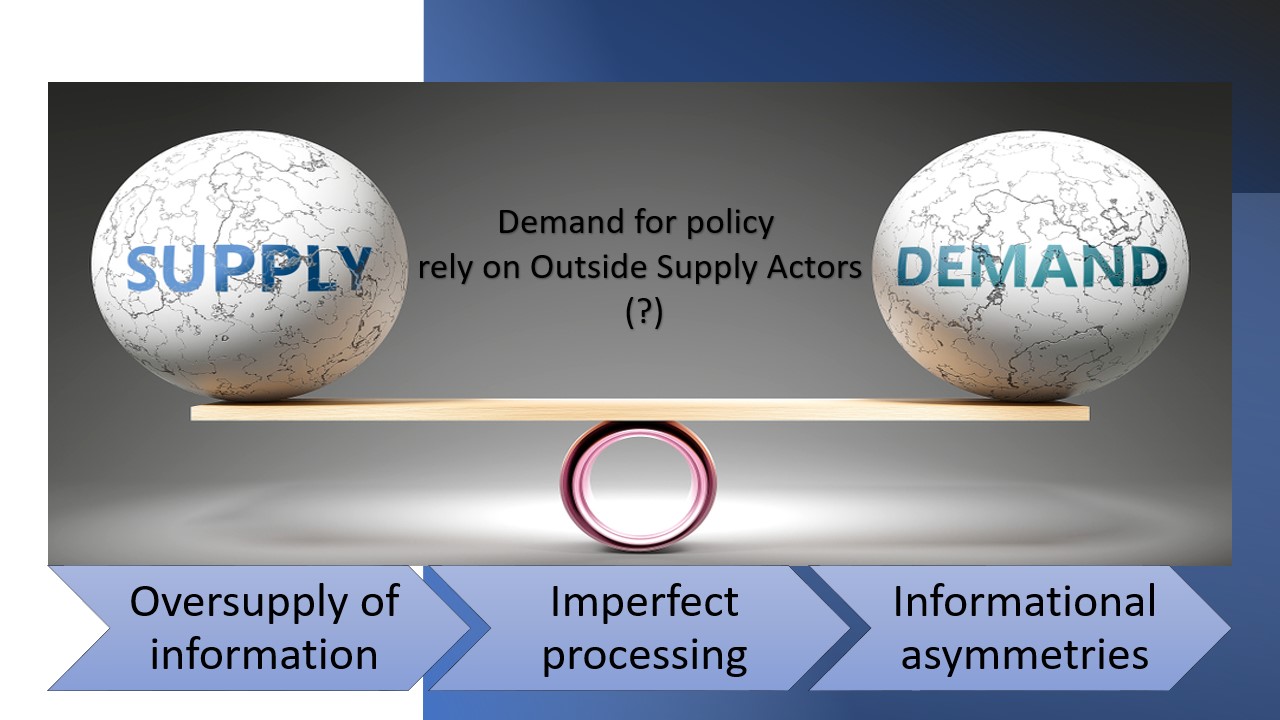

Supply and Demand for policy is distorted. The demand for policy relies on outside supply actors. This results in an oversupply of information, imperfect processing, and informational asymmetries that become a system feature. On the supply side, policy ideas are developed with partisanship rather than accuracy in mind. Outside groups tend to act along party lines, and the information base for policy is degraded. As a result, policy battle lines become harder, making compromise difficult, and partisanship has replaced credibility. The process has become more political, focusing less on writing good policy papers and more on advancing and selling ideas. In this policy market, sellers often possess more information than buyers.

On the demand side, consumers often lack the knowledge to understand the quality of goods and services they receive. Members of parliament lack the resources and desire to process overwhelming amounts of information. Parties tend to formulate policies to win elections rather than winning elections to formulate policies. Staff members are often selected based on political connections rather than policy expertise. Additionally, information is often sought to justify pre-existing beliefs or policies.

Power of Politics in Structuring Your Advocacy

Political parties can provide a structured approach across various issues or an unstructured pluralism. Policy outcomes are often shaped through arrangements between policymakers and activists, forming “governing networks” or co-drivers. Politicians set the parameters within which outside organizations produce and disseminate policy issues. When politicians lack clear directions, “research organizations” and policy entrepreneurs can step in to fill the gap and provide evidence-based solutions in cooperation with the political actors.

Indeed, the prevailing trends indicate that organizations have shifted towards employing direct advocacy and marketing strategies. The rise of ideologically motivated organizations has garnered increased influence. Organizations are embracing greater public engagement. Influence appears to be more concentrated within organizations with clear partisan preferences. Academic organizations face marginalization within the current landscape.

Political Context Related to Policy-Making Context: role of development organizations

Understanding the political climate and its implications is crucial to advocate in such an environment. Distinguishing between pluralism, bias pluralism, and polarization helps determine the appropriate advocacy strategy.

Our advocacy role is to enter the existing “governing networks” (or build them) or the constellation of ties among policy entrepreneurs (academics, think tanks, and political organizations) and political actors that lead to policy change by developing and providing objective evidence. In this context, our partner’s role is to initiate campaigns and activism. In a project setup, our role is to provide them with “scientific knowledge” to pressing public problems, neutral information, and maintain a distance from political debate.

Advocating in a polarized society requires adaptability, a clear understanding of the context, and the ability to communicate ideas effectively to bring about meaningful change, fostering constructive dialogue and collaboration among diverse stakeholders.

This article expands on the Regional Network of Advocacy (EEU/WB). The Regional Advocacy Network would like to thank the key contributors Jonathan Ellis (campaigner, UK), Biljana Jovichevich (Media & PR, Montenegro), and Anica Aleksova (Educational Policies & Governance Expert, North Macedonia), who shared their valuable experiences from our projects in Montenegro and North Macedonia.

Interested in learning more about the advocacy network? Contact us at AdvocacyWesternBalkans @helvetas.org.

Resource Materials: